The Print Issue

Editor’s Note

by Aria Kothari

I’ve never had any sisters—or siblings, for that matter. Growing up, I never had to share my bedroom, or my bathroom, or any of my toys. In a capitalist world in which individualism and exclusivity are of high value, growing up without having to share presents itself as extremely desirable. It removes competition and sacrifice from the equation: no siblings means no fighting over the front seat, no comparing Christmas presents, and no competing for parental validation. There’s undoubtedly perks of being an only-child, but as only-child will tell you—given the chance—it’s undeniably lonely. Individualism ultimately promotes isolation, and while my friends envied for a life without siblings, I always yearned for a life with. We’re conditioned to want what we can’t have, after all.

I now live in a college dorm with four other roommates. We share our bedrooms, our bathrooms, and perhaps most principally, all of our clothes. Our shoes are squished together in a towering rack, our laundry is often littered across each other’s bedroom floors. Our closets have become one—as have our kitchen ware, and our room decor, and our food. We spend most of our nights together in our living room, talking and laughing and procrastinating our schoolwork. I’ve confided in them and bickered with them and traveled with them, and ultimately, I’ve grown to love them. I am so very thankful to share my home with these women, but I am most thankful that they’ve become the sisters I never had.

“Sisterhood” is a visual and literary collection of works encompassing the beauty and entanglement rooted within female friendship. In the spirit of sharing, this issue was made in collaboration with my friend Becca Solomon, a woman who’s always treated me like a sister. “Sisterhood” is dedicated to her, and to all of the beautiful and wonderful women featured in this issue.

xoxo,

Origins

by Aria Kothari

My mother went to college in the late ‘80s in the city of Pune, Maharashtra, India; “ready-made” clothes were unavailable and uncommon. Instead, my mother grew up going to the tailor, not the department store, for clothes. Her and her sisters would make a day trip out of the experience; twice a year, they would go to the tailor’s store where they would select fabrics and accessories and sift through catalogs containing patterns for all the latest styles of salwar kudtis— Indian blouse and pant sets that were popular womenswear at the time. After hours of measurements and choosing fabrics and buttons and dupattas, the three of them would leave the store having designed five new outfits to be worn for the next six months. A month later, each sister’s customized looks would be ready.

As a mechanical engineering major, a computer applications major, and a civil engineering major, my mother and her two sisters had a particular affinity for math. They devised a formula to maximize each of their wardrobes; each of them got to buy 10 sets of blouses and pants a year. If they combined their collections, the three of them had thirty outfits total. With six days of college and thirty outfits to choose from, each sister could go at least a month without repeating an outfit. Factoring in the outfits created from mixing and matching sets, outfit repeating became extremely minimal. They used their knowledge of calculating combinations to keep their closets trendy.

“My friends always thought I was so fashionable, because I was always seemingly wearing something new. As a young girl in a new college, it definitely boosted my self-confidence.”

There were rules to this system, to “keep the peace,” as my mother said. After an outfit was worn, it was the last wearer’s responsibility to get the garments cleaned and ironed within a few days of wearing so that it was readily available for the next sister. Outfits made of synthetic fabrics did not easily stain, so they could be worn anywhere, but outfits made of cotton were borrowed with a lot more caution.

“The way the shared closet worked, each garment belonged to one person and the other two sisters were borrowing that outfit. When I would wear something that belonged to one of my sisters, I took extra precautions…It forced me to take better care of my clothes in my day to day life.”

My mother and her sisters shared their clothes like this until they left home and split up after college to move to the United States. The ritual isn’t completely dead, though— my aunts’ visits to our home in California usually include a designated time of trading dresses and jewelry and accessories with each other. Now that I am in college, I’m constantly reminded of my mother and her sister’s practice. When I borrow my roommate’s dress before a night out, or a sweater for class on a cold day, or a pair of stocks when I run low in between laundry loads, I think of my mother and her sisters’ communal closet.

Communal Closet

by Becca Solomon

Sharing clothes is a radical act.

The patriarchy, like any oppressive structure, thrives on the in-fighting of the oppressed. By pitting women against each other, not only is time and energy misplaced and wasted, but the negative qualities assigned to women are embodied and reaffirmed. The patriarchy tells us that women act “catty” and “jealous” to one another because other women are an obstacle to male attention—since everything women do is obviously done for male attention. Fighting amongst women, when viewed within this patriarchal framework, confirms this notion. Such a framework, of course, is both heteronormative and extremely shallow in its understanding of female relationships. It uses a capitalist principle of valuation which encourages scarcity: to increase value, one must be unlike other options. Ever been told “you’re so not like other girls” as if it’s a compliment? The patriarchy encourages women to be unlike one another and to fight to hold onto what makes them unique or desirable.

I’ll quickly note that I am analyzing the behavior of sharing clothes through the patriarchal lens and I recognize that. I am not doing so because I believe the premise that women dress for male attention, but because accepting the premise for the sake of argument allows for the logic of the patriarchy to be undone from within. There is undoubtedly power in the outright refusal of patriarchal logic. To say, it does not matter what women do with their clothing because it is not done for men is an important sentiment to share. But to say, even if we do dress for male attention, we still care about each other more than we care about you is valuable as well. It flaunts the solidarity that the patriarchy fears, showing that women care for one another enough to work around the ideology that was meant to tear them apart.

Sharing clothes acts as a big “fuck you” to a system that believes women should value male attention over female friendship. Within the logic of the patriarchy, a woman’s appearance is construed as currency in an effort to “win” male attention. Clothing, being a facet of a woman’s appearance, becomes something to withhold and protect as capitalism encourages one does with currency. If male attention is the number one (and maybe only) priority, it is vital that women hoard their currency. Clothes hold dual power as currency and as a potentially differentiating feature, making them even more important for women to keep to themselves if they desire male attention above all else. So what about when they don’t? Sharing clothes flagrantly deprioritizes men, making it a radical act of care within a patriarchy.

A woman’s capacity to care is, in itself, a complex quality within a patriarchy. Little girls grow up caring for dolls in order to prepare them to nurture their future children. These future children are expected to be the product (and, in many ways, property) of a man; a man who is cared for by his wife and who was once a little boy being cared for by his mother. As a little boy he was never given a doll because, unlike a little girl, he was never expected to nurture. If the patriarchy wants little girls to provide care and to grow up to marry a man, who cares for the little girls when they become women? The men these women were told to focus their attention on never learned how.

In spite of our male centric instructions, we women step in for each other. We don’t withhold care because the duty to provide it was forced upon us, we share it. Care is a beautiful act; one that the patriarchy cannot define or take away. When we were meant to be learning to care for a child by playing with dolls, we learned to care for each other too. We learned to care for each other by dressing dolls and to dress each other by caring for dolls. We refuse to give up the act of care but we deny patriarchal reasoning for it, turning care itself into a radical act. As cheesy as it sounds, sharing (clothes) really is caring.

Resistance does not have to be taxing. Often it can be truly joyous. To find joy in that which the dominant system deems “less than” is radical. Dressing is made out to be a woman’s duty under the patriarchy. It is mandated that women must dress well in order to please men, but those who find joy in the act are degraded as vain. The choice to frame a love of dressing as vain serves a dual purpose in subjugating women. To find joy within a structure meant to take it away is extraordinarily dangerous to that structure. As a result, the ability to find joy must be portrayed as a negative trait. Vanity carries with it the necessary negative connotation, but also speaks to a woman’s love of herself. Not only does an accusation of vanity work to undo the joy found in clothing, but it insinuates that a woman having pride in herself is a bad thing. The underlying assumption that vanity is bad does the work of naturalizing the unnatural. It treats a woman’s self love as inherently harmful. Finding joy in clothing challenges the desire of the patriarchy to strip joy from the lives of the oppressed and exposes the negative implications of vanity as a tool for the degradation of women.

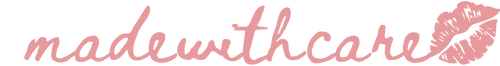

The refusal to compete and radical care that is implicit within the act of sharing clothes (and even more so by the assumption that all clothing is communal) is beautiful to behold. “Girls of all genders,” to borrow Carina del Valle Schorske’s phrase, come together to make each other look and feel as good as possible. I have sacrificed numerous outfits because I could tell that a friend wanted to wear my skirt more than I did. I have dressed a friend head to toe, telling her (truthfully) that she looked great in everything we tried, but nonetheless putting together outfit after outfit until she felt she looked great. I have announced that I am in need of silver jewelry with my outfit and been bombarded with offerings from friends. These moments of solidarity create a place for women entirely separate from their relation to men; a place with one another. In an effort to protect this place, I vow to continue to give and receive with reckless abandon and I sincerely hope you will too.

Common Thread

by Becca Solomon

Throughout girlhood, clothing ties us together. Put girls in close proximity, give them a place to go, and, more often than not, clothing will be exchanged. The beautiful thing about being entangled through clothing is that the same thing bonding you to others is simultaneously providing you with agency. Clothes allow you to define yourself without words. In new situations, you are often seen before heard; your style is the only part of a first impression that is within your control. What you do with your style is an assertion of autonomy in the face of assumption. For me, clothes ease the pressure to “perform” in new social situations. If I can win people over with my style before speaking, I am less desperate to impress verbally (and trust me, my desperation certainly does NOT impress).

For a long time I felt as though I had to choose one identity and keep it consistent. If I wanted to be smart, I could not dress “girly.” According to society (and practically every teen movie I ever watched) these were mutually exclusive traits. As I grew older, I found power in rejecting this false dichotomy. However, the “either/ors” do not let up. We must be individualist or collectivist. Isolated or entangled. Alone or clone. In the US, collectivism is associated with uniformity and loss of identity; individualism is put on a pedestal but leads to isolation and unrealistic expectations for oneself. In a society where independence is praised, it is seen as a weakness to rely on others. So what happens when we all rely on each other? Mutual reliance becomes collaboration. We share and then we make it our own. We are entangled individuals.

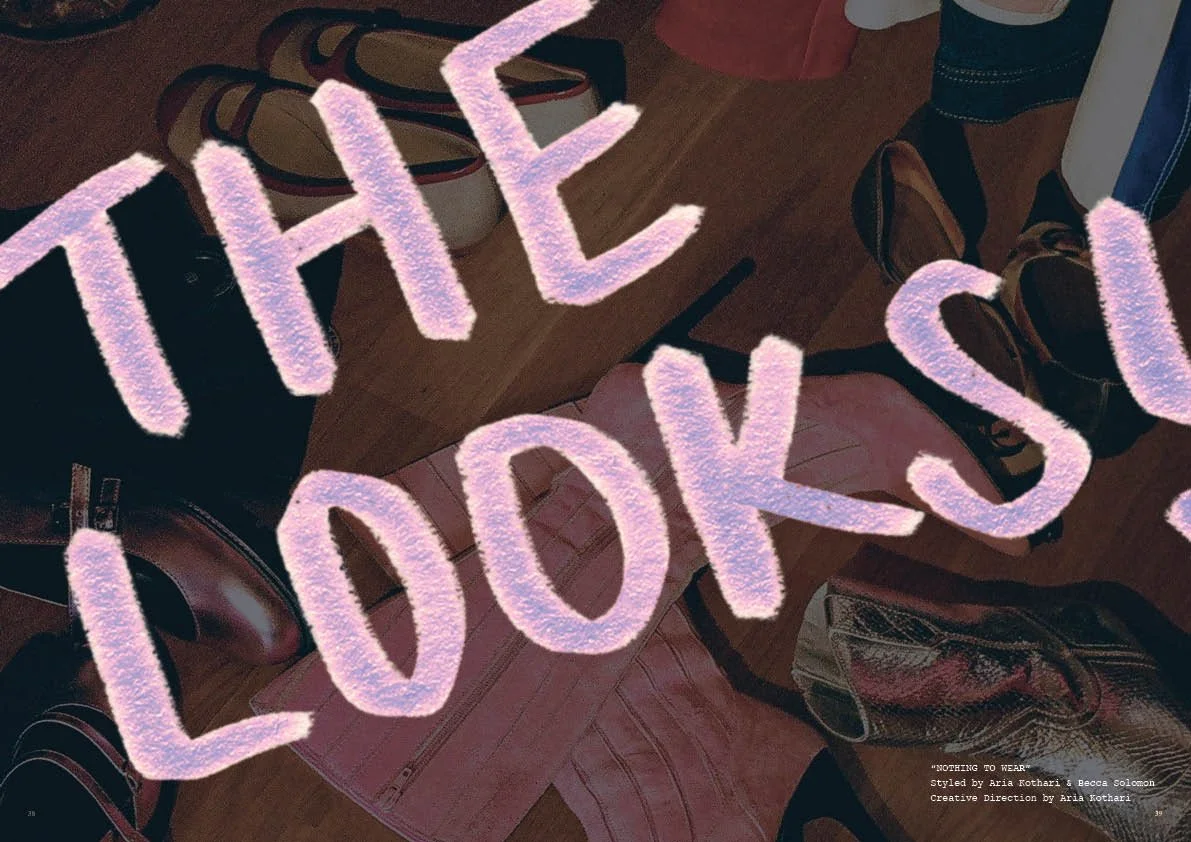

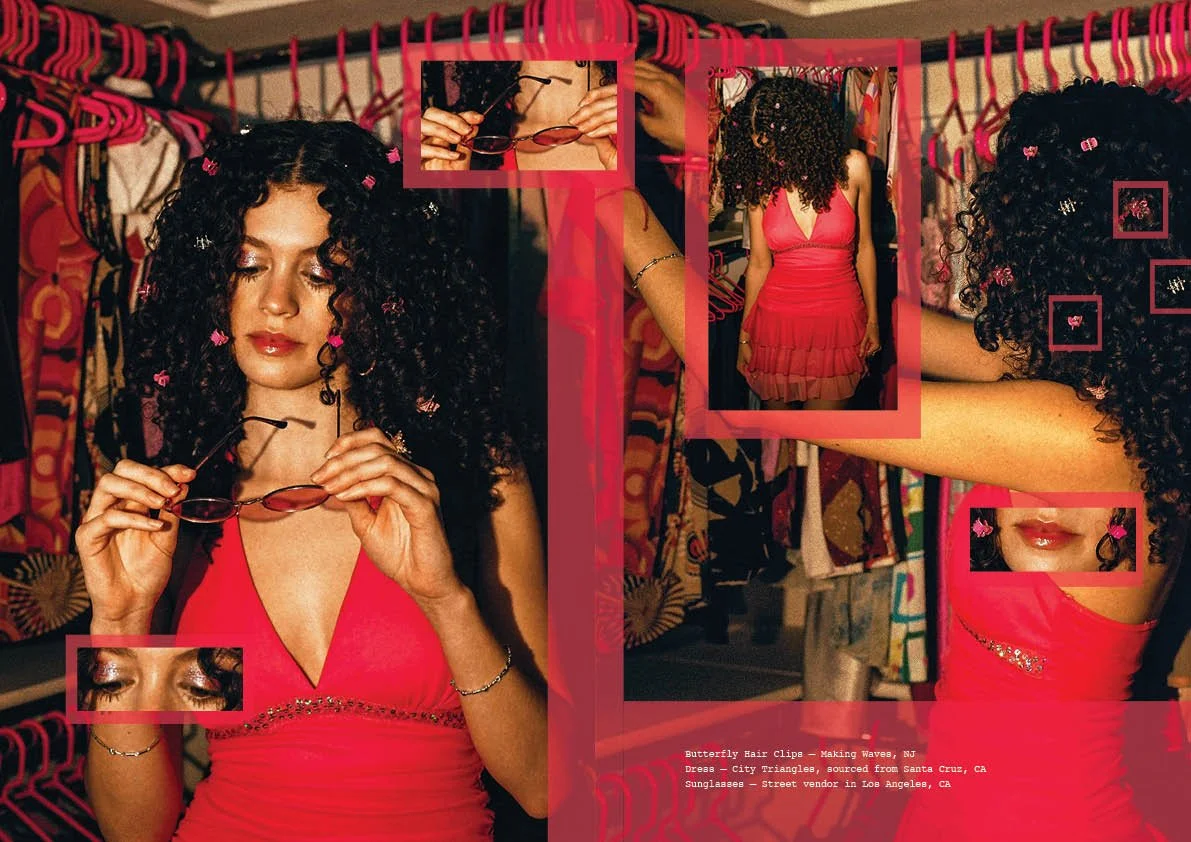

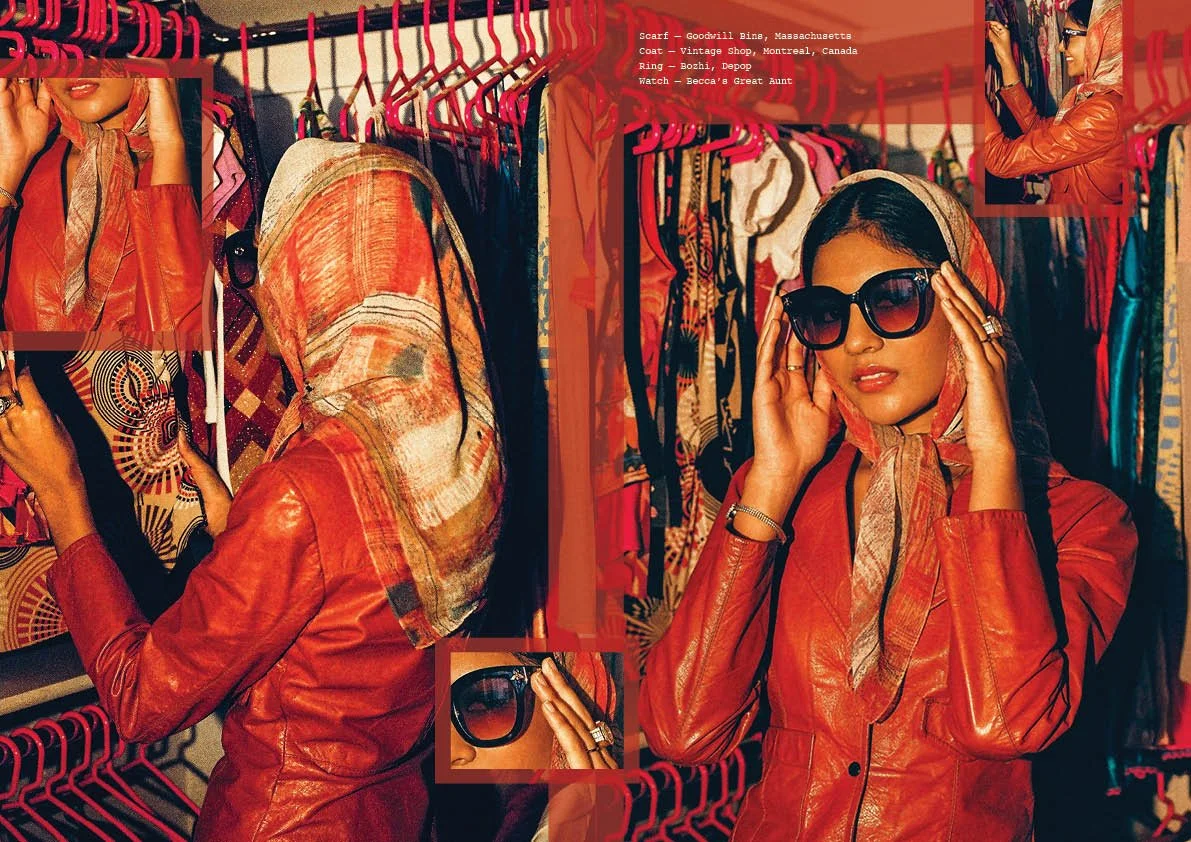

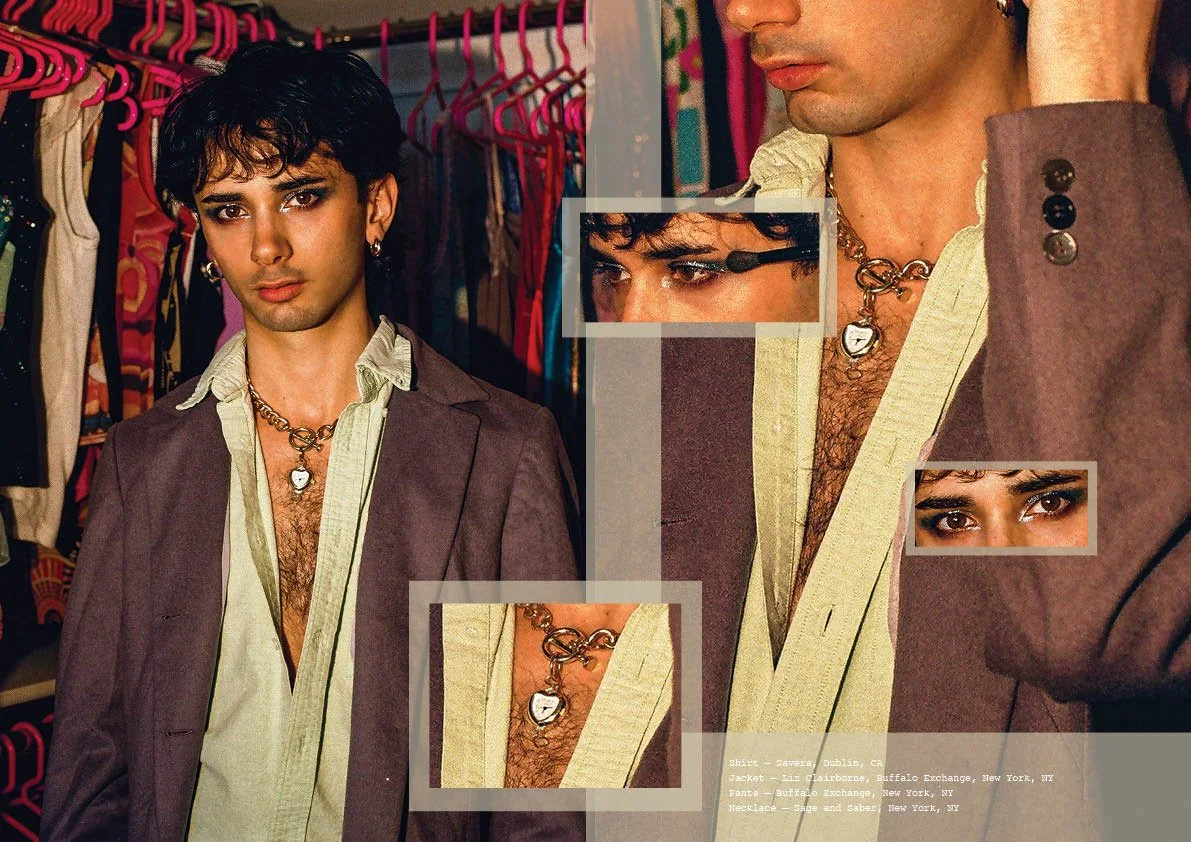

In this section, models were told to choose their own outfit incorporating the same pink tie. They arrived on set in an array of different colors, styles, and tie placements. From headband, to belt, to traditional necktie, individuality shone through and yet the common thread was just as central. When we borrow a piece of clothing and “make it our own,” we know that next week someone else can make it just as much theirs. To share clothes is to collectively deny the concept of exclusive ownership, a concept invented by and for capitalism. If capitalism is a game, then the way to “win” is to hoard assets and the “prize” is isolation. Opposing the “game,” even just by treating your closet as communal, creates and/or strengthens community within a society built to pull people apart.

The refusal to be pulled apart is symbolized in the shared tie. Just as the tie wraps around and through itself to create a knot that resists being undone, a shared garment ties us to each other, entangling us until bonds become hard to undo. In literary analysis, a “common thread” is a recurring element in different areas or bodies of work. It connects the unconnected, noticing similarities across genres. In fashion, thread holds garments together. It stitches sleeves to bodice to skirt. The tie is our common thread, it connects us as we are, without categorizing, and holds us together like this.

What’s TIE-ing us together?

Acknowledgements

Co-edited by Becca Solomon

Written by Aria Kothari & Becca Solomon

Fashion by Aria Kothari & Becca Solomon

Designed by Aria Kothari

Photography by Sarah Wills

Modeled by Megh Basu, Emma Duchesneau, Aashi Khandelwal, Desmari Miller, Jack Teehan, Sueah Whang, Leigh Wolbergerm